By Bishakha Datta

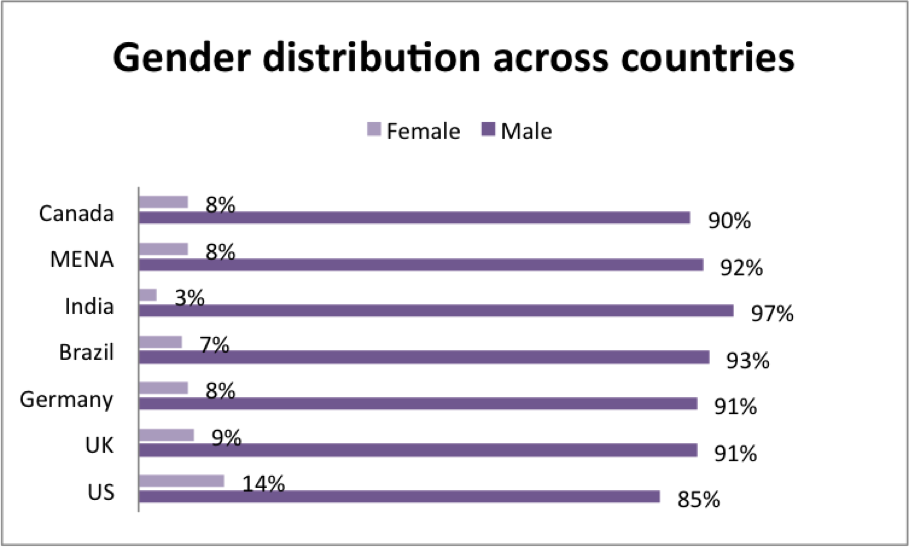

Three years back, we found some evidence of what we intuitively knew: most Wikipedia editors are men. A 2010 survey of more than 175,000 users and contributors showed that 87% of those who ‘edit’ or write wikipedia are men; only 13% are women. Granted, the respondents were self-selected, not random, so these numbers may change with a different set of respondents. Even so, the numbers showed a sizeable gender skew in who creates knowledge – and by extension, in what gets coded or reproduced as knowledge.

The Wikipedia Editors’ Survey of 2011 (graph above) confirmed these findings. But as with all data, the bigger question is always: So what? Does what the data tell us really matter? Does it mean anything if more men than women create an encyclopaedia? Shouldn’t we, as Wikipedians, be more concerned about ensuring that an encyclopaedia read by 500 million people is accurate, comprehensive, easy to use and access, instead of worrying about who creates it? Shouldn’t we focus on filling in the knowledge gaps that exist instead of bridging the gender gap?

No way. All of this goes hand in glove, like mac and cheese. In a peer-based model which relies on the bits and bytes of information that each of us brings, the ‘who’ is just as important as the ‘what’. So if the computer science pages on English Wikipedia are strong, it may be because editors who care about computer science showed up at the table, male or otherwise. If the pages on Bhuleshwar, a historic neighbourhood in Mumbai or on Flavia Agnes, a noted Indian feminist are still stubs, it may be because no one who cares enough about these has yet shown up. If one page recently went from ‘Chelsea Manning’ to ‘Bradley’ and back again to ‘Chelsea’, it’s partly a function of who showed up to discuss the issue of naming trans persons. It’s the who thing.

Look behind any Wikipedia page and you’ll get my drift. When more editors from Kerala enter the picture, Malayalam Wikipedia grows. When more LGBT editors tune in, those pages improve – among others. We need more women to write up their worlds on Wikipedia for the exact same reasons. With one big caveat: this is not about boxing women into gendered roles and assuming they’ll only write about ‘womanly’ issues or lipstick or fashion. Some may choose to write about packet-switched networks. Or about probability, like the editor in this video. That’s what we really want, the diversity and the fullness of it all. The whole nine yards.

Ok, so now that the dogs of data have let loose the gender gap, where do we go from here? We need to know more; understand why women aren’t editing in large numbers. Is it the editing interface? That women are too busy? That women lack confidence and don’t see themselves as ‘knowledge creators’, which sounds kind of like a heavy dress to wear? Is it the culture of Wikipedia, which can be fighty and argumentative? Is it that editing is kind of isolated, not social? Is it the culture of open source projects, which opens certain doors that then close others? Watch Alyssa Wright analyse a similar gender gap on OpenStreetMaps in this video:

Chances are it’s all of the above, and that it’s different for different women. Not just chances, but every bit of evidence – from the anecdotal to the numerical – shows that all these need to be tackled to make a dent in the gender gap. Lots of stuff is already underway: a new easier-to-use visual editing interface; the TeaHouse project, which welcomes newcomers and supports them until they find their feet; edit-a-thons on under-represented themes such as women scientists; the WikiWomen’s Collaborative on Facebook and twitter and what not. In San Francisco, a bunch of women turned an edit session into a party. In Jerusalem, a group of women edit every Monday over snacks and laughter. Most important of all: we didn’t ignore the data. We took it on. We started taking small steps towards ensuring that we provide the sum of all human, rather than male, knowledge.

Sucheta Ghoshal teaches her grandmother to edit Wikipedia

Bishakha Datta is a Bombay-based writer and filmmaker and the executive director of Point of View, an organisation that includes the points of view of women in media, arts and culture. Bishakha also serves on the board of the Wikimedia Foundation. She tweets as @busydot