Tactical Tech has been delivering digital privacy and security training for over a decade. In this time they have produced a series of toolkits and guides on this topic and have trained hundreds of Human Rights Defenders. We are asked Chris, a digital security trainer at Tactical Tech and one of the developers of the Security in-a-Box toolkit, five questions we consider pertinent for rights advocates considering using technology to implement Transparency and Accountability initiatives.

Q1. If I was doing a project that makes use of open data that has been made available by the government, are there any kinds of privacy and security risks I should consider? I mean if it’s open data, surely there can’t be too many issues to think through, right?

The results of any project that involves sorting, aggregating, cross-referencing, prioritising, contextualising and/or visualising data is potentially sensitive for the same reason it is potentially useful. Regardless of whether or not the information was publicly available (and even if it was widely known), the act of analysing and presenting it creates knowledge. Which, of course, is why we do it! Accordingly, when planning an open data project, an activist or journalist should consider not only the privacy implications of the project’s final publication, but also the operational security concerns inherent in data collection.

Here is one way to think about this admittedly non-intuitive category of privacy risk: while doing research for an open data project, one could at any moment stumble upon a story about a clueless government or a careless corporation whose ill-considered publication of data about its citizens or its customers threatens to put vulnerable populations at risk. While this story would clearly be worth pursuing, it is not difficult to see how privacy considerations would factor into every stage of such a project.

In short, I would advise folks using Open Data not to assume that the organisation (government or otherwise) who provided the information has carefully thought through the implications of its release—or, for that matter, that they even know what is in it.

Q2. What if I am crowd-sourcing data from the public in a project that is scrutinising the government in some way. How might I work through thinking about possible risks?

When crowd-sourcing data that will be used to put pressure on the government of the people from whom those data were obtained, one should set a rather high bar for what constitutes “informed consent.” It is increasingly clear that many governments have both the technical expertise and the financial resources necessary to collect practically all Internet and mobile phone traffic from within their borders. Furthermore, the confidentiality offered by strong encryption is of limited relevance to this particular threat, as merely being associated with the project through traffic analysis or meta-data collection could prove sufficient to incriminate those who have contributed to the crowd-sourcing effort.

It may be worth singling out text messaging (SMS) here, as a medium that is particularly fraught, in this respect, as it:

- consists of short, keyword searchable strings of text

- relies on a centralised infrastructure with a built-in system for archiving (billing-related) meta data

- has been subject to monitoring and surveillance by governments for a relatively long time

- is frequently used in crowd-sourced data gathering campaigns.

It’s one thing to ask people to submit information that may incriminate a government agency in some way; it’s another to ask if they are willing to be directly associated with the claims being made. We should not assume that an answer to the former request implies a similar answer to the latter. For this reason, risk and consent must be carefully considered.

Q3. How can rights advocates find a balance between taking advantages of the opportunities of networked technology and open data and the associated risks? I mean when you give digital privacy and security workshops are you a bit worried of scaring people into inaction?

Yes, I do worry about this! Seeking a balance can be quite difficult. But, the point of security is not to minimise risk, it is to maintain agency. Without that, we lose more than just our ability to protect ourselves, our communities and our partners; whether we know it or not, we lose our ability to affect change. That is to say, an activist needs to make conscious, informed decisions to ensure that she retains the freedom—the “elbow room,” if you will—to be an activist. There are rarely clear answers, and any decision may be the correct one, depending on the circumstances, but it certainly doesn’t hurt to have a baseline level of understanding about digital security and privacy issues.

Q4. Is there any point in making yourself secure if all the people you are communicating with aren’t doing the same? I mean doesn’t it come down to the weakest link in your chain of communication?

Think about it this way: the odds are extremely slim that everybody in your network will suddenly improve their security at the same instant, which means somebody has to take the first step. So it might as well be you.

Q5. What are your top 3 favourite digital privacy/security tools and why?

Truecrypt: At the cost of a little extra time when settling in for a stretch of work on my laptop (or, occasionally, on someone else’s computer), I gain the peace-of-mind that comes from knowing that my most sensitive data are protected by strong encryption, and will not be compromised by a lost, stolen or confiscated laptop or USB drive.

Ostel: This secure voice-over-IP (VoIP) service, combined with the CSipSimple application for Android, provides end-to-end encryption and allows me to use something other than Skype when having one-on-one voice conversations with other Ostel users.

ChatSecure (formerly Gibberbot): While the off-the-record (OTR) plugin provides end-to-end encryption for several instant messaging applications (Pidgin, Adium, etc.), none of them are particularly fun to use. ChatSecure for Android is a nice, simple way to have at least one secure communication tool with me at all times.

Chris works for Tactical Tech (@infoactivism) and his digital security team sometimes communicate about digital security issues with @ONOrobot

Additional Resources:

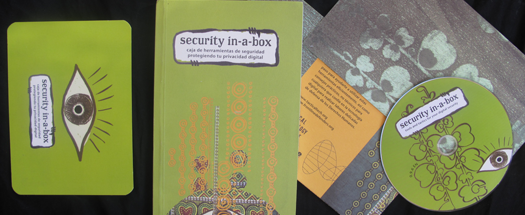

Security in-a-box

Survival in the Digital Age

Me and My Shadow