On August 1st 2013, three Sri Lankans were shot and killed by the army in a village called Weliweriya. The villagers had come out onto the street to protest against a local latex factory contaminating their drinking water. Local papers reported that before teargas and shooting began and before the army stormed a church to beat (and in one case kill) hiding villagers, the army Brigadier commanding the operation told the villagers: “Do not try to photograph or video when we disperse the crowds. If you do that, we will smash your cameras.” The footage we were able to see online is of people running or staying to hold their ground and of people being shot by the military.

The fight for justice continues in Weliweriya, just as it does in thousands of similar, unfolding stories around the world where people are often fighting simply for a liveable environment.

When we started to think about creating an environment issue for the Micro-magazine, we started by talking not only about unfolding stories like Weliweriya, but also some of the key moments in environmental advocacy history that continue to resonate for activists today.

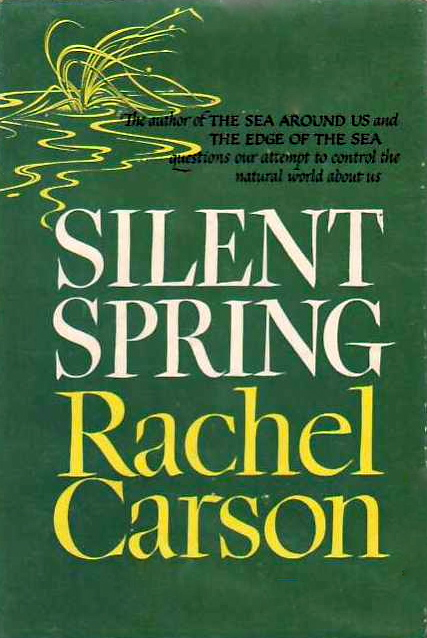

First, we spoke about Silent Spring, a book released in the 1970s that reveals the deleterious effects of the use of commonly used pesticides like DDT on the environment. While the author, Rachel Carson, received criticism from some quarters of the scientific community for the claims she made, Silent Spring was one of the first books that directly took on industry and their role in environmental degradation by citing scientific evidence.

Next, we discussed the organised, grassroots resistance to the destruction of forests in India in the 1970s known as the Chipko movement. The name of this movement comes from the Hindustani word chipko, which means ‘embrace’ or ‘cling to’ as the villagers, particularly women, put their bodies between the machinery and the forest – literally hugging the trees. Chipko made a strong statement about our individual and collective responsibilities to organise to protect natural resources and our local ecologies.

The third element of advocacy we discussed was the visual and which images have been particularly significant for the environmental justice movement. We remembered our own responses to a particular series of images of the planet taken at different points in time and with different implications. ‘The Blue Marble‘ image was first taken in 1972 by the Apollo 17 mission. When it was declassified by NASA and released to the public, our blue planet suddenly looked solitary, vulnerable and in need of protection in the face of growing evidence of degradation. A decade later another set of images of the planet began to circulate, this time showing a hole in the ozone layer above Australia and Antarctica and the term ‘greenhouse effect’ entered our everyday language. These images sparked rallying moments for the environmental movement.

Going back to past moments in environmental advocacy and dwelling on unfolding battles has helped us to think more crucially about what is and is not changing in terms of the use and value of evidence.

While Weliweriya villagers had collected evidence of the pollution to their drinking water, this did not prevent government officials from ignoring them, court actions being stalled or villagers being beaten and killed. Sometimes, as this case indicates, it isn’t enough to collect evidence; the question is what more do we need to do to create impact with this evidence, particularly when we’re working within hostile political contexts? What are the promises of data for addressing environmental abuses and how does working with data for advocacy introduce new obstacles when we know that scientific evidence can be manipulated, challenged or disputed, as the skepticism around climate change shows?

The digital and physical security implications of information-activism needs to be considered before activists pick up a camera or download a spreadsheet. This point resonates clearly in this issue’s stories about Silas Siakor and Marcelo Marquesini. Silas Siakor explains that he had to flee Liberia after releasing evidence that linked the government to natural resources corruption and arms trading. Marcelo Marquesini reveals that fellow campaigners have been murdered because of their efforts to protect the Amazon rainforests.

Beyond thinking about security risks, as we come to launch this publication we have been pressed to think about governmental abuses of international laws and protections that allow activists to protect environments where ownership and jurisdiction remains contested. The Russian government is right now holding 30 Greenpeace activists after their peaceful protest against Arctic oil drilling. Russian armed security forces boarded and seized the Greenpeace boat in international waters, which many legal experts argue flagrantly disregards international treaties. Shockingly, the Russian government are charging at least some of the peaceful environmental activists with piracy and if found guilty, they’ll face up to 15 years in prison.

All of these challenges to environmental activism highlight the importance of the work featured in this issue. We’d like to thank all of the contributors for generously sharing their knowledge and experiences with us in bringing you this first issue of the Evidence and Influence Micro-magazine. We would love to hear your feedback, thoughts and experiences on the questions raised through this issue.

Tanya Notley (@tattinot) and Maya Ganesh (@mayameme), October 01st 2013.