At Camp Rajwat set up a stall one night to screenprint T-Shirts. The design she printed on our shirts was one of many that she and fellow campaigners used as part of Mashaa, a campaign fighting to save the seashore as public spaces in Lebanon. Here she tells us how the seashore is being transformed and occupied happening and what Mashaa are doing about it.

The story of Mashaa began in 2012, in the middle of a hot and sticky summer in Beirut.

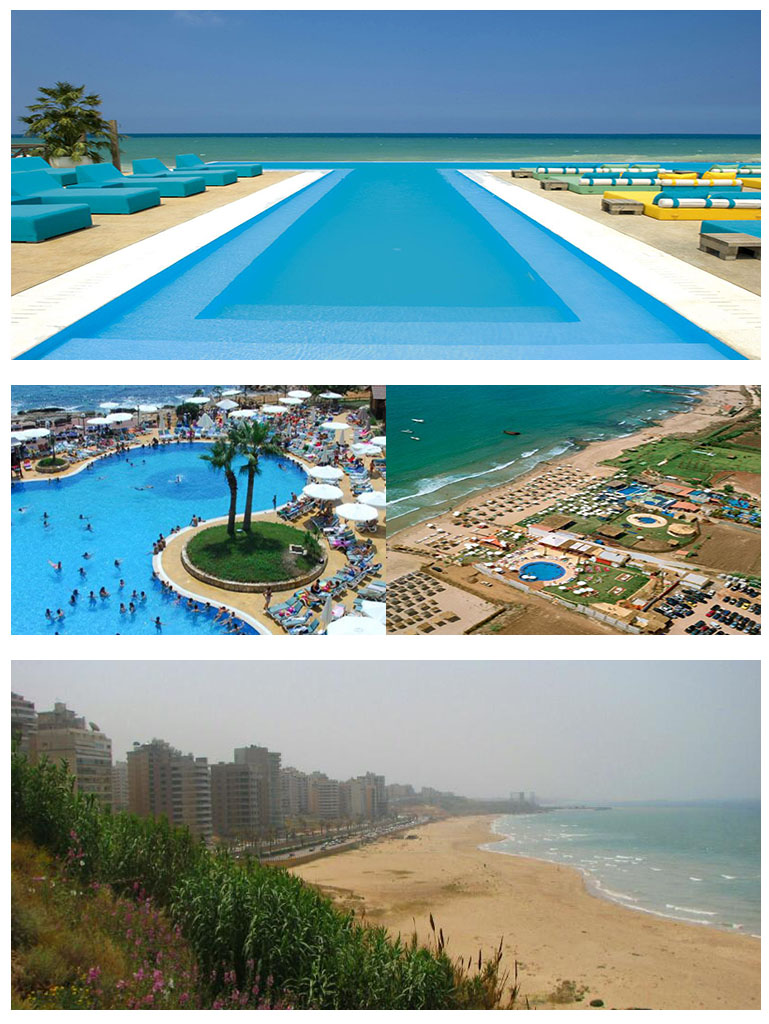

It came at the end of a decade. A decade where we had witnessed, all along the coast, new chic beach resorts popping up like mushrooms, with swimming pools and jacuzzis right on the sea, bars and bartenders serving cocktails from inside the pool to the loud beats of techno music.

Images left to right: (top) view from top of the pool, beach resort in north Lebanon, beach resorts in southern Lebanon, (bottom) Ramlet el Bayda (the white sands) the only accessible public beach left in Beirut, that was also bought and will soon no longer be public.

In the last few years, things had started to accelerate. Prices started rising insanely. Getting access to the beach can today cost us up to US$40, per person. Just to access the beach!

It was about this time when we realized that the beach does not belong to us anymore. We are being forced by developers to pay money to access the beach, even though the Lebanese law – like most countries in the world – clearly states that access to the beach should be free and open to everyone.

Some of us, faced with this injustice, grew frustrated, but surrendered by saying ma hayda libnan (‘but this is Lebanon’). Others chose to act on these frustrations, hoping that they can change things. It is in this context that a group of economists, journalists and activists met in August 2012, and started preparing for a big event; a sort of end-of-summer party. The idea was to use it as a launch for the campaign and movement we decided to call Mashaa’ (‘the commons’), that seeks to stand against any occupation of public spaces in Lebanon, and to work actively on regaining public spaces specifically along the seashore.

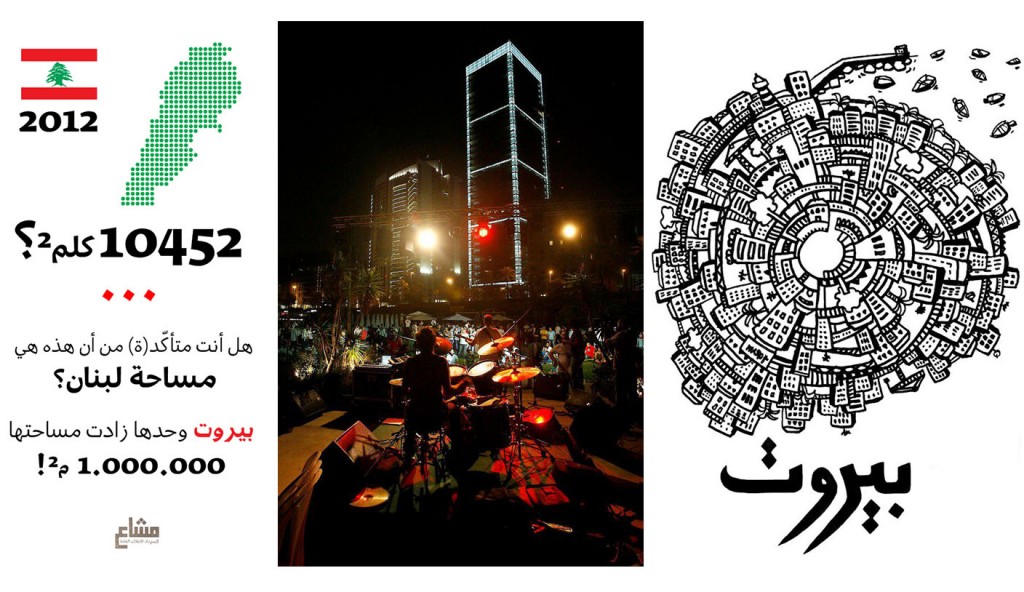

The launch’s aim was to attract a wide range of people, especially young. It wouldn’t be yet another monotonous political meeting under a ceiling fan and neon lights. We would invite designers, illustrators, artists, musicians, and performers, and we would have fun.

The preparation for the launch of the movement started with a one month research on laws, stories and data concerning the occupation of the company Solidere in downtown Beirut, followed by one month of event preparation, during which an open call was launched for artists from all over the country and outside to participate in our campaign. These two months allowed us to investigate and then illustrate what was happening so we could communicate our cause. We produced posters, t-shirts, postcards, graffiti, animation and a manifesto that contained our vision and details of the research we carried out.

Finally, the party took place on September 28, on the St Georges Bay. It was open to everyone, and around 500 people attended where they saw live concert and heard or read our messages. (Also worth mentioning, a whole troupe of Lebanese army soldiers spent the night with us, to ensure the security and prevent any possible conflict with Hawk, Solidere’s private security guards).

Images from left to right: Graffiti stencil on the wall says “because they want to see the sea, we are not able to see the sky anymore”, live silkscreening of T-shirts during the party, posters distributed during the party.

Images from left to right: Info graphic projected on street wall says ’10542 km2? are you sure that this is the Lebanon’s area size? Beirut alone grew 1000000 m2!’, Live concert in St Georges bay, Postcard and T-shirt design by Jana Traboulsi.

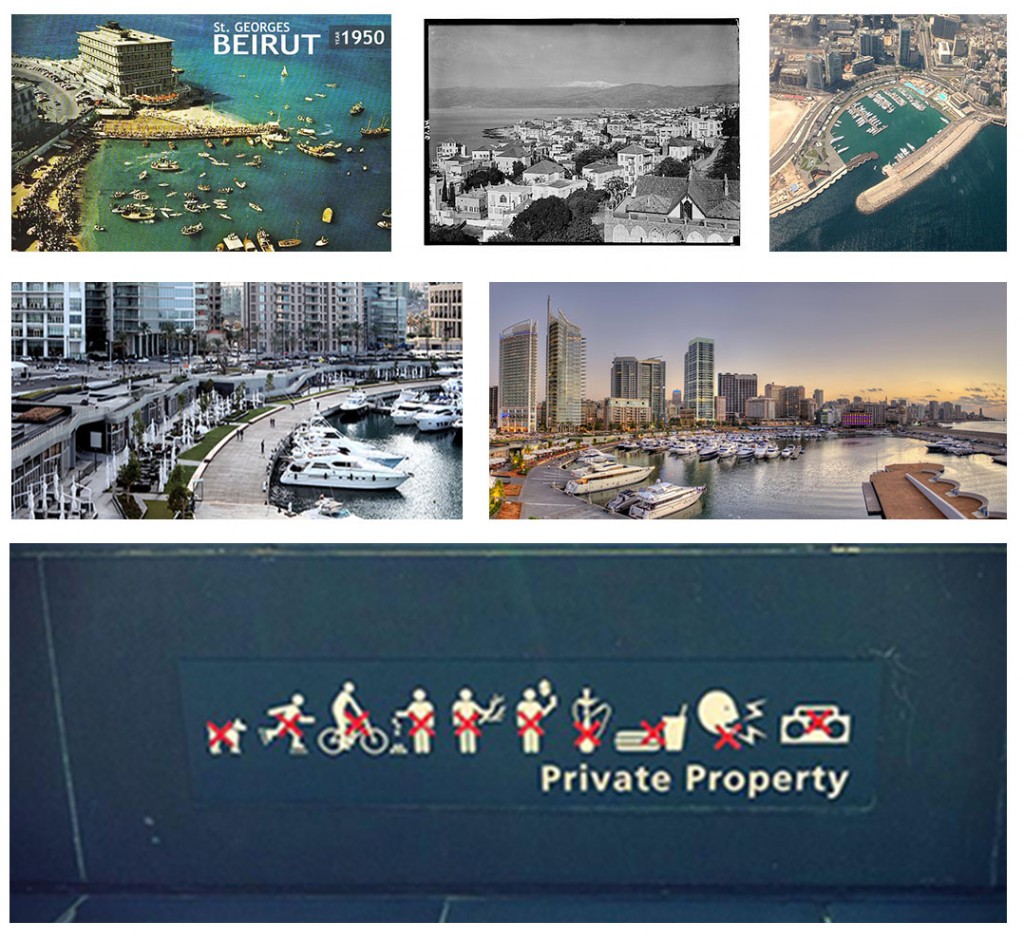

So why a party in St Georges Bay? Well, let me tell you the story of this ‘reclaimed land’.

In that same summer of 2012, we were all surprised with the opening in downtown Beirut, of “Zaitunay Bay” the Beirut waterfront project that took over the famous St Georges Bay, and turned 20,000 square meters of our public property, by means of landfilling the sea, into a private property (an open space with restaurants and a yacht club).

This reclaimed land is owned and was built upon by two companies: Solidere (50%), which belongs to the ex-Prime Minister, Rafik Hariri; and Stow Capital Partners (50%), which belongs to the current Minister of Finance, Mohamad Safadi, previously Minister of Infrastructure (that’s how they got the permit, you see?).

What does this suggest to you?

For us, it is a proof that some people have been working actively, using the power they have, to transform our public land into a private money-making business hub for themselves. We argue that, by law, any backfilled area is, and should remain, public property.

That is why, strategically, Mashaa chose to start campaigning around the backfilled Beirut waterfront, notably the area in between the western port, currently known as the Marina and the eastern port, which is still under construction.

Below the pictures of before and after this project can give you an idea of how our seashores are being altered and privatised.

Images top row: St Georges Bay in 1950. and (black and white image) Beirut before the 1975 war. Below: St Georges Bay as it looks today (right view from 3D model from Solidere’s website and left a real view of Zaitunay Bay today). Sign in Zaitunay Bay that lists the forbidden activities on what is now private property.

Images top row: St Georges Bay in 1950. and (black and white image) Beirut before the 1975 war. Below: St Georges Bay as it looks today (right view from 3D model from Solidere’s website and left a real view of Zaitunay Bay today). Sign in Zaitunay Bay that lists the forbidden activities on what is now private property.

Since this time, we’ve come across many new projects that are trying to copy the Solidere business model, and follow the same process. Watching how it works, we have learnt a few things about the usual patterns.

The scheme is simple, let me tell you how it works: a bunch of powerful businessmen band together; at least one of them is in the government, and he would be in charge of the legal side. He would (re)write the laws (i.e. make exceptions for the sake of the ‘public good’), or get politicians to approve the project in return for political favours, or even shares in the project.

Then the idea would be to “build land” on top of the sea water, made of rubble and pebbles from destroyed houses, or even garbage, or rocks from some mountain. Presto: you now have new waterfront property that bypasses existing laws about the public ownership of the seafront. Often here we notice the same phenomena: the land gets fenced and forgotten, with the gang just letting it sit until they think the time is ripe for development. In the meantime, the price of the land goes up, but also all lands around it: this is called land speculation.

This process not only changes the geography of the place, but also it’s demography. A clear line of separation between rich and poor areas starts showing up.

While we find this neoliberal model everywhere in the world, what is particular in the reshaping and theft of public space in Lebanon is twofold. First, Lebanon’s banking system runs under bank secrecy (in the same way that tax havens do), which in turn facilitates money laundering. Second, no taxes are paid on land transfer and land acquisitions, even though, in 2012 for example, the declared real estate sales were worth more than $9.2 billion (according to Ministry of Finance figures).

Lebanon is blessed with 220 kilometres of coastline. While this should be an asset for all Lebanese to enjoy, this coastline is now subject to constant violations. We have documented 1,140 encroachments along the beachfront – an average of 5.18 intrusions per kilometer. Only 73 of those encroachments are ‘licensed’ to privatise parts of this coast.

The construction and claiming of public land in Beirut, and all over Lebanon, provides a lucrative business for those who have power, control or sometimes just the ‘right’ connections, to accumulate massive personal wealth.

So what do we do now?

I think that now is about time we realise, that we do not have a state anymore. That we need to regain our state first because it has been hijacked by a group of people (the warlords as we call them, and they are not more then 300) accumulating their wealth from our public properties and using our taxes to pay their bank interest while they do so.

As for Mashaa movement, beyond researching laws and figures (that we eventually expose through local medias), Google Earth became an indispensable tool to actually identify the places and names of the violators. Through it, we started scanning the 220 km seashore to get a real picture of what is really going on the coast, sometimes physically visiting the site. The first picture we published on our Facebook page, was a screenshot of a small house that looked suspicious because of a half circle levee that blocks entirely the seawater area facing it. When we published the picture on our Facebook page, along with the coordinates and address of the house, the obvious question was, “to whom does this belong?”

A screenshot from Mashaa’s Facebook page asking people to identify the owner of the house and the circular levee

We received a lot of answers from people who lived in the same area; some saying it was a wealthy Lebanese who made his fortune in Africa, others answering with the same question. Eventually we found out, with a half-surprise – thanks to an unpublished report about occupants of the seashore done by the Ministry of Infrastructure, that the house belongs to gentleman named Nabih Moustafa Berri – who is no other than the head of the Lebanese parliament since 1992 and founder of the Amal (‘dispossessed’) movement.

We are currently processing all the data we gathered through official reports and also facebook posts and messages that were sent to us from citizens to inform us about public spaces violations in their areas. We are planning to build an interactive map that will show the names and faces of those who are occupying our Lebanese seashore. We hope this will give Lebanese citizens a clearer picture of who is benefiting from these developments and how this directly connects with our political system.

Additional Resources:

Stay up-to-date via Mashaa’s facebook group

Design studio, maajoun, explains how they came up with their design for Mashaa, using the research collected for the launch.

Listen to people explaining why they are fighting for public space in Beirut

This news story examines what is happening and uses Google Earth to assess new developments

This news story examines some of the worst seafront violations

Each square meter of land on the Marina port (which is public property by law) is being rented out to Solidere for 2500 LBP per year (less than $2USD). This short animation that was part of the Mashaa campaign asks the simple question: what can you buy for 2500 LBP?

Story by Rajwat – Mashaa